More and more parents have been told by police that an individual with access to their child or children is a sex offender — but some believe the current law does not do enough to protect children.

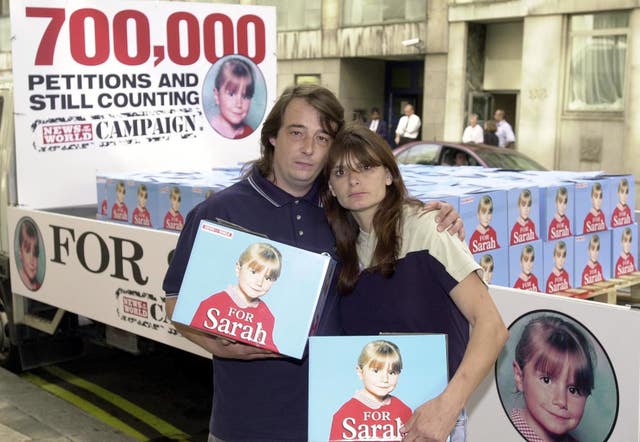

Sarah’s Law, officially known as the Child Sex Offender Disclosure Scheme, was introduced following the abduction and murder of Sarah Payne, eight, by paedophile Roy Whiting, in 2000.

It allows anyone to ask their local police force if someone has a record of committing crimes against children.

Such disclosures have nearly doubled since the law was introduced in 2011, rising from 120 a year to 219 annually, according to comparable figures obtained under freedom of information laws by Portsmouth University’s journalism department.

Out of the 46 forces, including the British Transport Police, in the UK, 22 returned comparable data, revealing at least 1,140 disclosures have been made to parents since 2011.

However, when including the partial data returned by some forces, figures suggest it could be much higher, with at least 1,427 adults informed someone close to their child has a history of sexual offences since 2011.

There have been complications, with one mother taken to court after using the scheme and subsequently outing a paedophile neighbour in 2017.

Claire Varin, a mother of two, became suspicious of a new neighbour after he knocked on their door and asked if their eight-year-old daughter would like to go berry picking with him.

She contacted West Yorkshire police and discovered he had previously been jailed for possessing child abuse images.

Under the conditions of Sarah’s Law, Ms Varin was made to sign a non-disclosure form, preventing her from warning anybody else. However, after her neighbours found out, she was taken to court.

She told the PA news agency: “It makes you question how effective the law is. It’s meant to be there to protect children, but we can’t share the information – technically you aren’t even supposed to tell your partner, although the police did accept I was going to do so to protect my children.”

The charges were eventually dropped, but following the ordeal, Ms Varin separated from her partner and moved away from the street she lived on.

She said: “We were just left to deal with this information. We were told a paedophile had moved onto the street and we were expected to just live with it.

“The person who is disclosed to, how can you sit back and just watch them interact with children? You are just as bad then, it is on your conscience.”

“The stress of it all meant I didn’t want to live there anymore. He refused to move out until just a few months ago,” the 37-year-old carer added.

“All I had done was what anyone else would have done.”

Applications under Sarah’s Law can be made by anyone, but the police will only inform the person who is able to protect the child.

So, for example, a grandparent may enquire about their daughter’s new partner, but the police would then inform the mother, not the grandparent, if the partner was found to have a history of sexual offences.

From the year the law was introduced to the last financial year, 8,958 applications were made by members of the public based on 22 police forces who supplied comparable data.

However, incomplete data from other forces suggests the total number of applications from across this period was at least as high as 16,900.

The proportion of applications that resulted in disclosure remained the same, at 14%, in both 2011/12 and 2018/19.

28 forces returned comparable figures for the last three financial years, which show a 29% increase in applications over this period and a 57% increase in disclosures.

Donald Findlater, director of child abuse helpline Stop It Now!, said it was “reassuring” to see the figures growing.

Mr Findlater, who sat on the panel consulting with the government before the scheme became law, told PA: “I think the rise is demonstrating a level of interest in safeguarding children and seeking information greater than we have had historically.

“I would like to see this trend continue because it is demonstrating awareness and vigilance.

“One in 10 children experience sexual abuse and one of the biggest problems is people are blind to the reality of it and think, ‘it won’t happen around here’.

“The fact that people are making the applications demonstrates to me that people are aware that the children they love and care about may be vulnerable to abuse.”

Even if an application does not result in a disclosure, those who enquired are given a pack with information about where to turn if they suspect abuse.

Mr Findlater said: “If a disclosure is not made, that is not saying to someone ‘you don’t need to be concerned’, because they might have a concern that is a legitimate one, he just hasn’t been arrested for something yet.

“Right now there are approximately 59,000 people on the sex offender register, but that is simply a fraction of those who represent a risk to children. Just telling a parent, ‘this person is not on the register’ is not telling people not to worry.”

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules hereComments are closed on this article